Report starting point

CircusInfo Finland and The Finnish Youth Circus Association surveyed the number and job titles of professionals working in the field of circus. The survey spanned the year 2017. Data was collected from the largest employers in the field, from vocational institutions and youth circuses, and by inviting individuals working in the field to answer a questionnaire.

CircusInfo Finland conducted the survey in 2018. The Finnish Youth Circus Association conducted an employee survey among its member organizations. Arts Promotion Centre Finland provided help and expertise at different stages.

There are no compiled statistics of professionals working in the circus sector in Finland. Statistics produced by Statistics Finland do not differentiate between circus professionals and professionals in other cultural fields. Arts Promotion Centre Finland does compile statistics of grant applicants by cultural field. Since only part of professionals working in the circus sector apply for grants, the grant applications received by Arts Promotion Centre Finland do not give a truthful and comprehensive view of the employment status or jobs titles of circus professionals.

The circus sector has grown, changed and become more versatile over the past ten years. Circus has grown both in relevance and numbers, be it as part of performing arts, basic arts education or the physical and artistic leisure time activities of Finns. The survey aimed to update data on the number of professionals working in the field and to form a picture of the circus sector as employer in Finland in 2017.

Circus sector employers in Finland

The survey gathered data on circus as job creator from the largest employers in the field: youth circuses, educational institutions that offer a degree in circus arts, circus companies that receive government subsidies and the Cirko – Center for New Circus, Dance Theatre Hurjaruuth, traditional circuses, CircusInfo Finland and The Finnish Youth Circus Association.

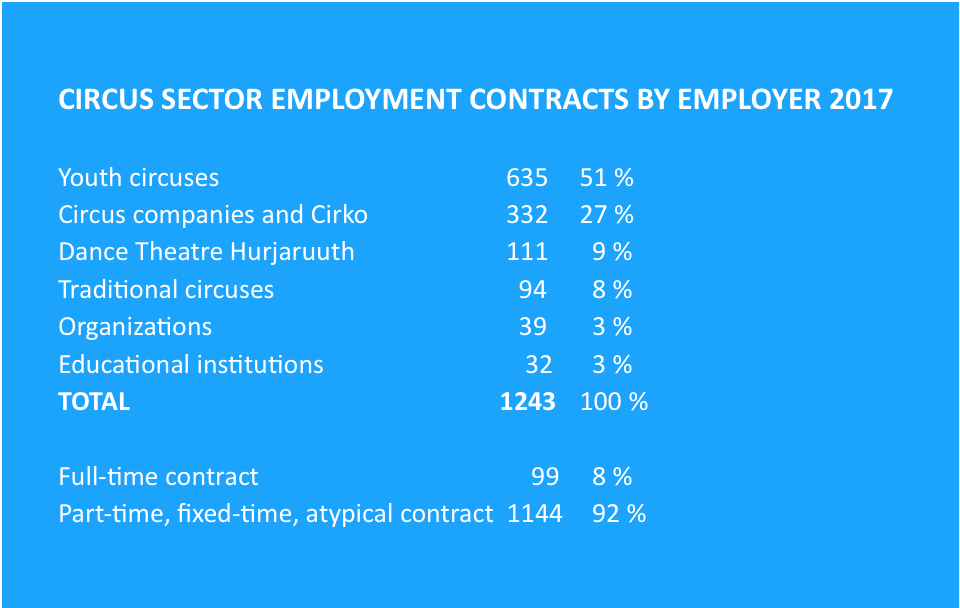

The circus sector employers surveyed offered a total of 1243 employment contracts in 2017. A total of 99 employees (8% of contracts) were full-time. Of the full-time employees, 69 worked in one of 17 youth circuses 3 worked in one of the two educational institutions that offer a degree in circus arts, 6 in either Cirko – Center for New Circus or one of three circus companies, 8 in Dance Theatre Hurjaruuth, 9 in one of two traditional circuses, and 4 in two different circus organizations.

Part-time, fixed-term or atypical employment contracts accounted for 92% of all contracts (1144 employment contracts in all). Of the part-time, fixed-term, or short-term employees, 566 worked in one of the 43 youth circuses surveyed, 326 in Cirko – Center for New Circus or in one of the ten circus companies surveyed, 103 with Dance Theatre Hurjaruuth, 85 in one of the two traditional circuses, 29 in one of the two educational institutions and 35 in one of the two circus organizations.

The number of contracts does not reflect the number of professionals employed in the field of circus, since the data does not account for overlaps. Individuals surveyed may have worked in multiple organizations over the course of twelve months while both performing and teaching. The data does, however, help form an indicative picture of the volume of circus as employer in Finland. A closer look at the number of individuals with a degree in circus and data gathered from professionals surveyed complements the picture.

Professionals with vocational education and training

The survey on individuals with vocational education and training in circus arts identified 318 Finns or foreign nationals working in Finland in 2017 who had received vocational education in the field. A total of 264 individuals had graduated from either Salpaus Further Education or the Arts Academy of Turku University of Applied Sciences (and their predecessors) between 1994 and 2017. In addition, four professionals had studied in Finland without earning a degree, and 93 had received vocational training abroad, 43 of whom had also studied in Finland.

Two Arts Council of Finland reports, by Merja Heikkinen in 1999 and Riikka Åstrand in 2010, have touched upon the number of professionals working in the field of circus in Finland. Heikkinen surveyed the 134 members of artist organizations in 1998. Åstrand’s survey, conducted in 2008, covered 205 individuals who had either gained a degree in or were currently studying circus arts. Our 2017 survey identified 318 individuals with vocational education and training in circus arts and/or pedagogy, a gain of 100 in ten years. Self-education is one way to enter the field. Furthermore, individuals with an education outside the circus sector may work in administrative and production jobs or in pedagogy. A survey targeted at professionals aimed to expand the overall picture.

Survey on jobs in the circus sector

CircusInfo Finland and The Finnish Youth Circus Association conducted a survey targeting professionals working in the circus sector in Finland and Finns working in the field abroad in 2017. The survey included all job titles in the field and could be taken anonymously either in Finnish or English. A total of 663 individuals were surveyed, and 244 responded (37% response rate). Only 220 respondents were trained professionals or people employed in the circus sector. A breakdown of the respondents’ answers:

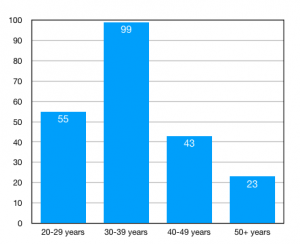

The average age of respondents was 37 years. The largest age bracket was 30-39 years (45% of respondents), followed by 20-29 years (25%).

A majority of respondents lived in the Helsinki metropolitan area; 9.5% of respondents lived abroad.

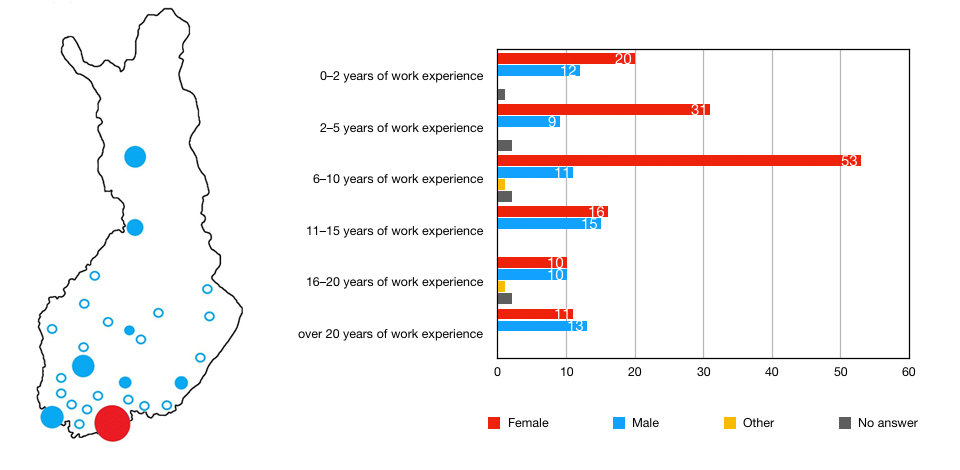

A majority (65%) had worked in the field for less than ten years, and 35% more than ten years. There was a significant overrepresentation of women in the less than ten years in the field cohort compared to the 10+ years cohort.

192 out of the 220 professionals worked in artistic or pedagogic jobs. 133 had vocational education and training, and 31% (59 individuals) worked in the field without having earned a degree in circus arts. Three out of four professionals without a degree in circus had a vocational degree from another field of study. 45% of respondents had self-learned and 39% had received on-the-job training. 35% of respondents had a background in youth circus.

Circus is a polymorphous field and jobs within the field reflect this versatility and diversity. Respondents named a total of 85 different job titles. The most cited were circus artist, teacher, performer, air acrobat, producer, magician, director, circus teacher and circus director. Circa half of job titles cited in the responses were performance-related. In addition to the aforementioned, titles included base, hair hanger, interprète, foot juggler, juggler, clown, flier, tightwire dancer, magician, and hoop dancer. Titles related to teaching and applied use of circus were cited 69 times (23%) and five times, respectively. The titles of artistic or circus director were cited eight times. Administrative and production work related titles were cited 32 times, and titles related to other arts were mentioned 16 times (i.a. choreographer, set designer, music and sound editor, actor, costume designer, composer, dance artist and teacher, light designer).

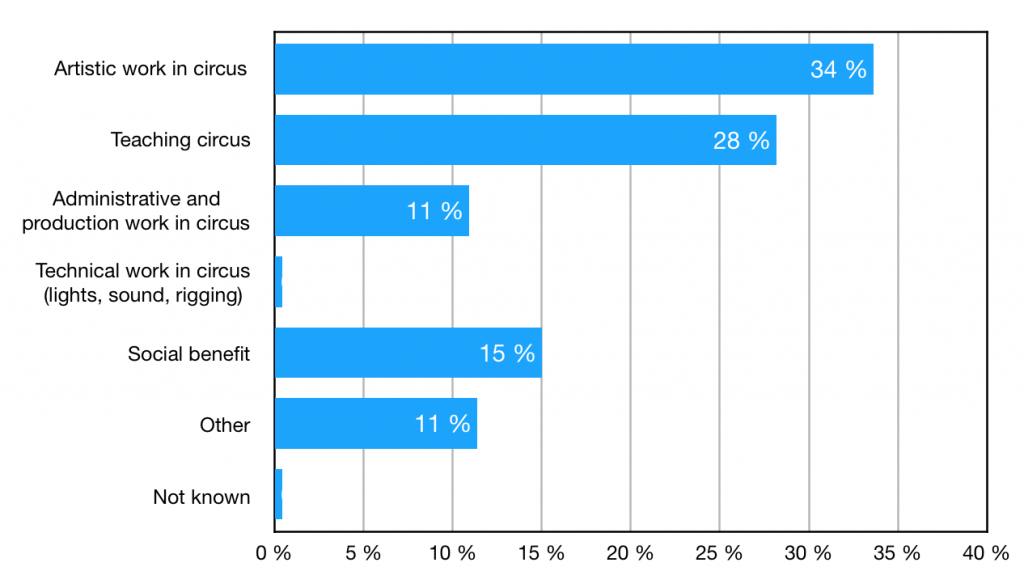

Employment and income

A third of respondents cited artistic work in circus as their primary source of income, and 28% cited teaching circus. Administrative and production work provided an income for 11% of respondents. A total of 161 respondents (73%) named work in the circus sector as their primary source of income. Social benefits and work outside the field provided the primary income for 58 respondents. In other words, the circus sector was not the primary source of income for a quarter of respondents. (Figure 5)

Grouping responses by jobs and years worked in the field shows how jobs in the sector are divided between individuals at different stages. (Figure 6)

Artistic work, teaching and administrative and production work, social benefits and work outside the field as the primary source of income were divided quite equally and proportionally between different brackets. In the top two brackets (i.e. more than 16 years in the field), artistic work was the primary source of income for more than half of respondents. Of all respondents, 28% cited teaching as their primary source of income, but a closer look between brackets reveals that teaching diminishes in importance as the years progress. Social benefits are more prominent as the primary source of income for those with less than ten years of experience than those with more than ten years in the field. 30 % of the recently graduated (with 0 -2 years of experience) cited social benefits as their primary source of income, a figure that diminishes as work experience accumulates. (Figure 6)

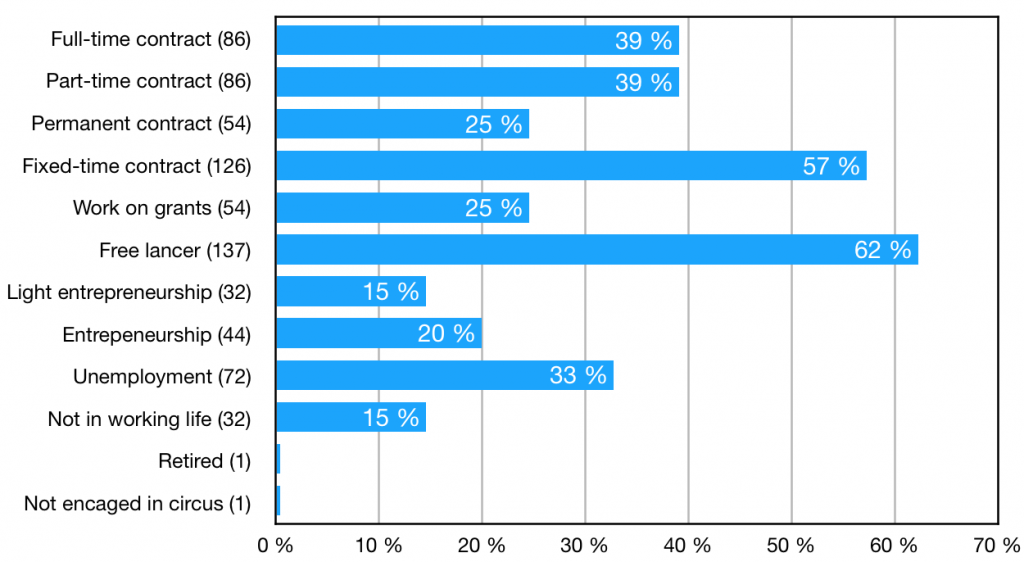

As employment and the nature of jobs available in the field may vary greatly from month to month, the survey asked respondents about their employment situation with a multiple-choice question. A majority of respondents (62%) said they had worked freelance. A majority of employment contracts (57%) were fixed-term. A quarter of respondents were permanent employees, most often working as teachers or in administrative and production jobs in youth circuses or circus organizations. (Figure 7)

The responses are in line with data provided by employers. Permanent employment in the field is associated with jobs in teaching and administration. Artistic work is almost exclusively fixed-term. Both the responses to the survey and data provided by employers highlighted the prominence of atypical employment contracts in the field. Close to half of respondents said they also worked jobs outside the field. A third had been unemployed.

Close to 50% of respondents reported having worked without pay. Unpaid work included technique rehearsals, rehearsing for a new project or production, and creative and artistic work. Administrative and production jobs could include doing unpaid work. Some of hauling, rigging, and service and maintenance related work was done without pay. Some of the unpaid work was voluntary or communal work, or work done in a position of responsibility.

The survey also highlighted how grants do not cover all work. Funds available often cover no more than performers’ salaries, and all other production related work is done without pay.

”Most (70-80%) of artistic work is unpaid work, and that is what it is for the most part. The salary is in the performance, grants cover but a small portion of work done. Also, much (30-50%) of administrative and production work is done without pay.”

”In theory, all circus artists do a certain amount of unpaid work, since you seldom get paid for rehearsing or upkeep even though it is part of the job. Office work is almost always done without pay. I do consider it work. It is certainly not leisure time…”

Job opportunities and working abroad

Organizations and associations along with circus companies and youth circuses were the most often cited job opportunity providers. They accounted for 50% of the responses to the multiple-choice question. Private sector gigs and odd jobs accounted for 17% of responses to the question.

Typically, circus organizations are independent arts sector organizations, companies and youth circuses. Their impact as job creators became evident in the question about job opportunity providers. Of the 453 responses to the multiple-choice question, 50% cited organizations and associations, circus companies or youth circuses. Performing at company parties and corporate events is an important source of income. Private sector gigs and odd jobs were cited as the most important job opportunity in 80 responses (17%).

A mere 39 responses cited arts institutions as important job opportunity providers. Currently, no facility in the circus sector is entitled to a statutory government transfer. Circus artists make guest appearances in theatrical productions, but theatres and other art facilities were marginal employers of circus professionals in 2017. Traditional circus was the number one employer in eight cases (4% of respondents). (Figure 8)

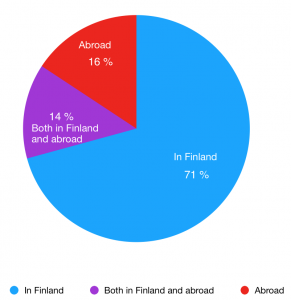

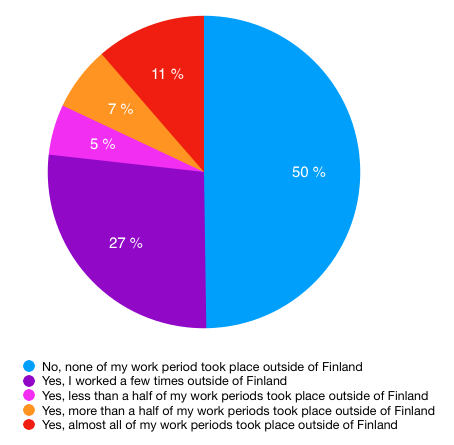

The survey revealed how a substantial part of job opportunities are jobs outside Finland. Half of respondents said they had worked abroad in 2017. Half of those who had worked abroad had worked for a foreign employer and the other half for a Finnish employer. For 11% of respondents, almost all jobs in 2017 had been outside Finland. (Figure 9.) 11% of respondents reported living abroad.

> Download this report (pdf)

> Read the full-lenght report in Finnish.For inquiries, please contact:

CircusInfo Finland, Johanna Mäkelä,